Wandering animals had to be impounded

Had this happened in 17th century Northamptonshire, there would have been a recognised procedure to be followed; Mistress Elizabeth would have been within her rights to drive Daisy to the village “pound”.

Most villages would have had a pound and they were generally used for the same purpose, although there were variations.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdFor instance, in Eastcote near Towcester, the pound, being close to the crossroads of Watling Street and the old Banbury Lane, doubled as an overnight holding pen for cattle being driven to market, probably at Banbury or Northampton.

But it was as a prison for wandering animals of all sorts that the pound was mainly used.

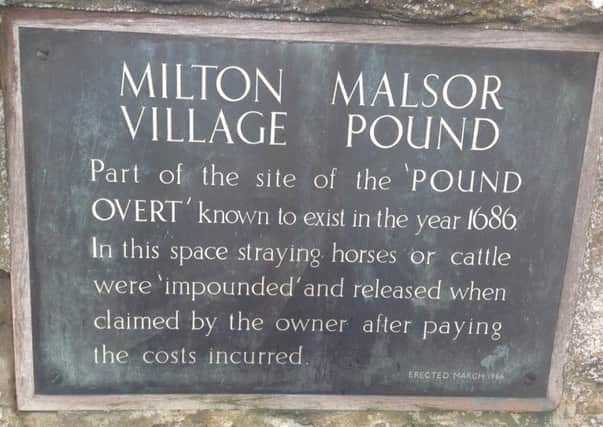

The most visible site for a pound locally is in Milton Malsor where, as my picture shows, a plaque had been erected to mark the spot.

Each parish appointed a man to look after the pound. It would have been fenced with a pad-locked gate and he held the key.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf animals were “impounded” he would let them in and if they were to be reclaimed by their rightful owner, again, it was to him that application must be made.

In Milton Malsor, the man with the key was known as the “pinnier” or “pynyerd”.

One report claims that Milton’s pound was big enough to hold up to 20 horses.

In some villages the pinnier or equivalent official would snap a stick in two pieces.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne piece would go to the farmer whose crops had been invaded by the animals, and the other part of the stick stayed with the pinnier.

Once the owner of the straying cattle found them missing, he’d be pretty sure where to find them, so he’d ask the pinnier who had impounded the creatures and then he’d go and see what damage had been caused.

He’d then be obliged to pay for the damage and, as a receipt, the aggrieved farmer would hand him his bit of the broken stick.

He’d then take the stick to the pinnier who’d join the broken bits together and if they made a perfect match it would be proof that the damage had been paid for.

But parishes were canny.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey charged a rent for each day the animals were impounded and only when that was paid would they be released to their owner.

We can still see evidence of pounds up and down the county.

Another plaque has been erected in Wollaston at The Cradle to show where the pound was during the mid 17th century, after it had been moved from a field next to the church.

The village pound in Yarwell has been given Grade II listing, and Pound Lane in Moulton and in Great Billing, and Pound House in Brixworth, all give us a clue about what went on there or nearby in centuries past.